Maryland is a lost village which could be found on the west side of Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour. Originally the island had been called Branksea but apparently so many visitors got off trains at Branksome by mistake that later the island became better known as Brownsea.

The lost village was named after the wife of its founder, Colonel William Petrie Waugh. The Edinburgh born Scot’s wife, Mary Murray Halloway-Carew was an amateur geologist. Apparently she was convinced after poking her parasol in the soil that the island held clay suitable for making high quality pottery. Former Indian Army officer, Waugh had decided to buy the island for £13,000 as a money making scheme. It is said he had returned to England with little property of his own. The purchase was after he had been told by a geologist that Brownsea Island contained a ‘valuable bed of the finest clay’ worth ‘at least £10,000 an acre.’ As Waugh was a recently appointed director of the London & Eastern Banking Corporation, he had little difficulty in continuously raising the funds for the ambitious project he hoped would make his fortune. It was also helpful that another former Indian Army officer and acquaintance, Mr J E Stephens was the bank’s managing director..

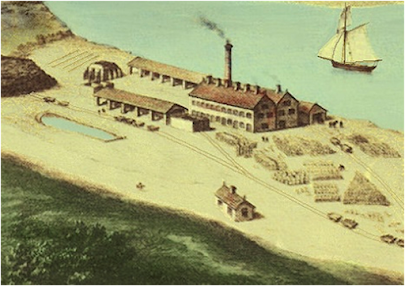

Colonel Waugh built the village of Maryland on the island to house his workers and also constructed a large pottery and brickworks. The village had a pub, the Bentinck Arms, which sadly closed in the 1920s and a village store. Waugh spent heavily on Branksea Castle and also constructed St Mary’s Church. A tall chimney made the pottery a harbour landmark and a pier, known as ‘Pottery Pier’ was built for the shipment across to Poole of his products. At its peak, the Branksea Clay & Pottery Company employed more than 200 people. While the kilns could fire up 70,000 bricks at the same time. Many employees rowed over to work daily from Studland. Sadly the clay, which was transported from the north of the island on a horse drawn tramway, was not of the quality that had been predicted. It was far better suited for the manufacture of products such as low priced sewage pipes, fire bricks and terra cotta pots rather than high value porcelain. It has been said that a high quality clay sample had been planted by the previous owner to raise the price of the sale. Colonel Waugh’s most ambitious work was to reclaim 100 acres of land in the St Andrew’s Bay area. He used over a million bricks to build a sea wall and put in a windmill pump to pump out the sea water. It was created to provide suitable grazing land for the Island’s livestock. Many years later, the sea would recover the area. In addition to his spending on Brownsea Island, he and his wife spent time in London where they gained a reputation for hosting extravagant banquets.

Financial problems came to light when a group of Poole tradesmen travelled over to the island to try to persuade the Colonel to stand for Parliament. He was away and his wife mistook them for debt collectors and pleaded for more time to pay. Following the tradesmen returning to the mainland, the couple were flooded with demands immediately to pay all monies due. The London & Eastern Banking Corporation was forced to close its doors with a £270,000 deficit and the Waughs fled to Spain. Between 1856 & 1863, Waugh made a number of appearances at London’s Bankruptcy Court and was jailed for 13 months after a career described as one of ‘emboldened magnificent expenditure.’ The Evening Mail in October 1858 wrote of Colonel William Petrie Waugh:

‘He set up the bank with a partner not with the intention …of

initiating an honest banking establishment but for the purpose of acquiring

access to a large heap of other people’s money in order that he might abstract

and squander it.’

An attempt was made to restart the pottery in 1881 but was unsuccessful and gradually the village of Maryland became depopulated. In 1927, Mrs Mary Bonham-Christie bought the island and closed down any remaining employment. During World War II, fires were lit at Maryland to distract German bombers from bombing Poole and Bournemouth. These so called ‘Starfish’ decoys were successful but the bombs did damage the deserted village such that the remaining buildings had to be destroyed.

The Victoria & Albert Museum in Kensington does hold a salt glazed jug made at Branksea Pottery around 1850. It had been given originally by Colonel Waugh to the Museum of Practical Geology. While on Brownsea Island’s south western side broken bits of pottery still litter the shore.

(Images: Branksea later known as Brownsea Island & Branksea Clay & Pottery Works.)

Comments

Post a Comment